Sharing Documents, Sharing History

“I didn’t fully appreciate the complexity of what I’d ended up doing,” Patrick Heffernan PhD, admits.

Patrick is a researcher at Historic Christ Church and Museum in Weems, Virginia.

In 2014, he began a project tracking slave histories, starting simply by recording historical letters on his personal computer.

Once this project began to take on a life of its own, Patrick realized he’d need a tool to help tackle the challenge of sifting through and cataloging the data.

When he found Knack, he “was just so delighted, impressed with how readily one could start to use it and how understandable it was.” Though he’d worked with databases some in the past, he “was very much a newcomer.”

In the years since, Patrick has used Knack to build a comprehensive app to store, organize, and analyze those slave histories, a project that has led to significant historical conclusions and allowed people to connect with their ancestry along the way.

I was just so delighted and impressed with how readily one could start to use Knack and how understandable it was.

Getting Started

Patrick’s work focuses on the Corotoman Estate, a large plantation on the Rappahannock River, not far from Christ Church.

What struck him about this estate was the number of documents in which slaves are actually named, rather than just counted. The level of detail in the historical documents was highly unusual: at each owner’s death was a complete inventory of his or her property, including slaves, who were often named and listed in family groups.

For Patrick, this was a massive discovery. It was a revelation, “the sheer density, the length of time, the distribution of all these compilations.” Immediately, he decided to start putting these into a database, “so one might be able to discern the individuals from the references.”

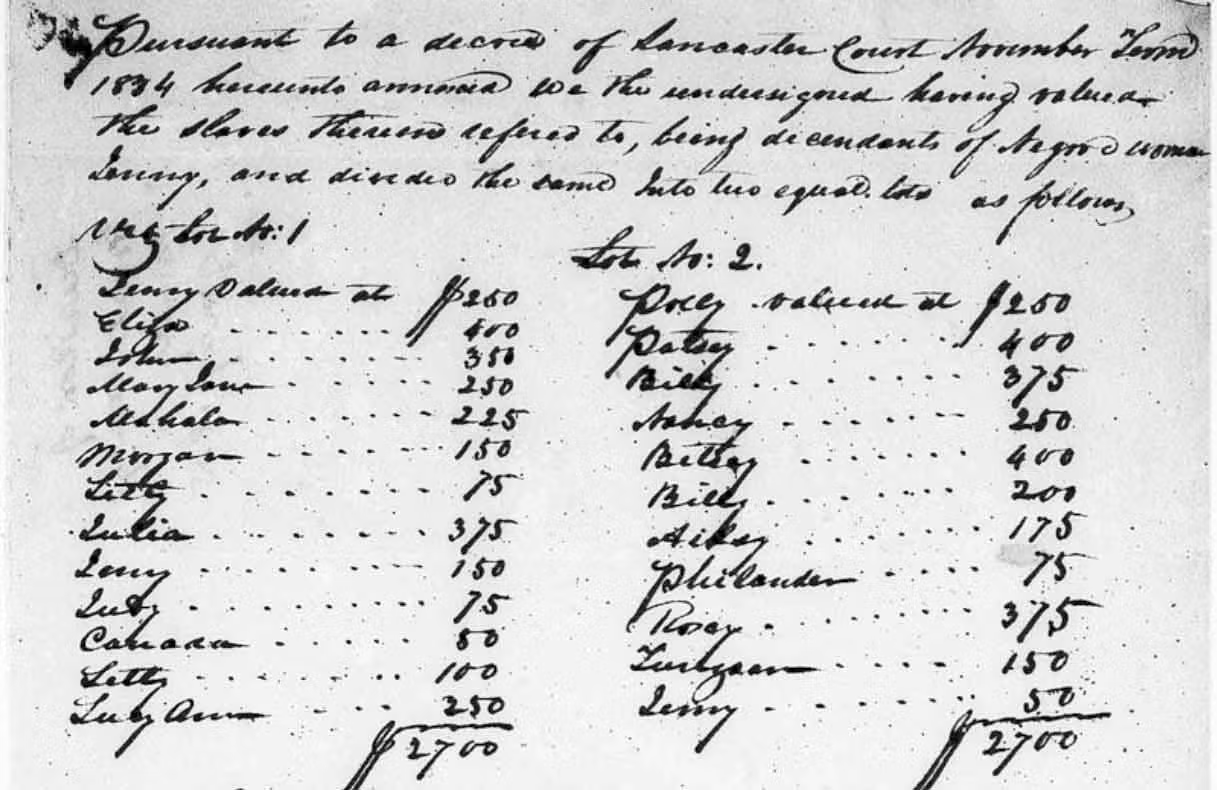

1835 court order dividing slave descendants.

Another historian encouraged Patrick early on in his project. This peer helped him realize the project’s historical potential, in particular for genealogical research.

That backing, coupled with his own passion for the project, has led Patrick to create an expansive database that’s entirely open to the public. Now anyone can search for a specific person, place, or time period to find relevant slave histories.

The creation of the slave histories database took about two years, as it required analyzing over 4,000 references to slaves who lived and worked at the Corotoman Estate, inputting the information into Knack, and building the app’s pages and navigation.

The Intersection of Technology and History

Distilling complex historical records into an easy-to-use application is always a challenge, but certain Knack features have helped to organize the app and make it more user-friendly.

Knack’s ability to navigate records and have it feel more like a website than a database is key. For example, selecting a document takes the user to a details page with a filter menu across the top.

“I just find those superb for the speed and the ease that they provide to any user,” Patrick explains. “I’m very happy with the fact that someone with almost no knowledge of using a computer can go to any page on this website and they’re able to quickly get to the information that they want without having to search or filter.”

Knack’s flexibility has also allowed Patrick to accommodate additional historical information.

Earlier this year, Patrick was visiting the Lancaster, Virginia courthouse when he spotted a book he’d never seen before. The book covered 1820-1834, and he knew that a slave owner, Dr. Charles Carter, had died in 1825, but the only inventory he’d seen of his estate had been done years later. Patrick opened the book and found a detailed inventory of Dr. Carter’s estate, including a “brilliantly clear” list of 65 slaves. He cross-checked with his own database, and sure enough, it was the first he’d seen of that information.

Carter inventory.

Discoveries like this one have helped Patrick further develop his app, as they give rise to new questions. For example, how would he link these new references to existing entries? Knack’s connections make it easy to connect different records together. Thanks to this new need to compound information, he “finally began to understand the joys of connections.”

This process enabled him to add important connected details for some entries, while making valuable revisions to others.

Sharing History with the Public

The biggest win for Patrick has been the opportunities his Knack app has provided to share his work with others.

“To have this online instead of in paper form at a library,” Patrick muses, “it’s contemporary, it’s such a valuable way to build knowledge. Other people are able to visit it and ask questions and add information.”

In late 2016, Patrick’s foundation held an event for the opening of a new exhibition at the small museum connected to Christ Church. Patrick’s work was on display that day, which led an attendee to seek him out.

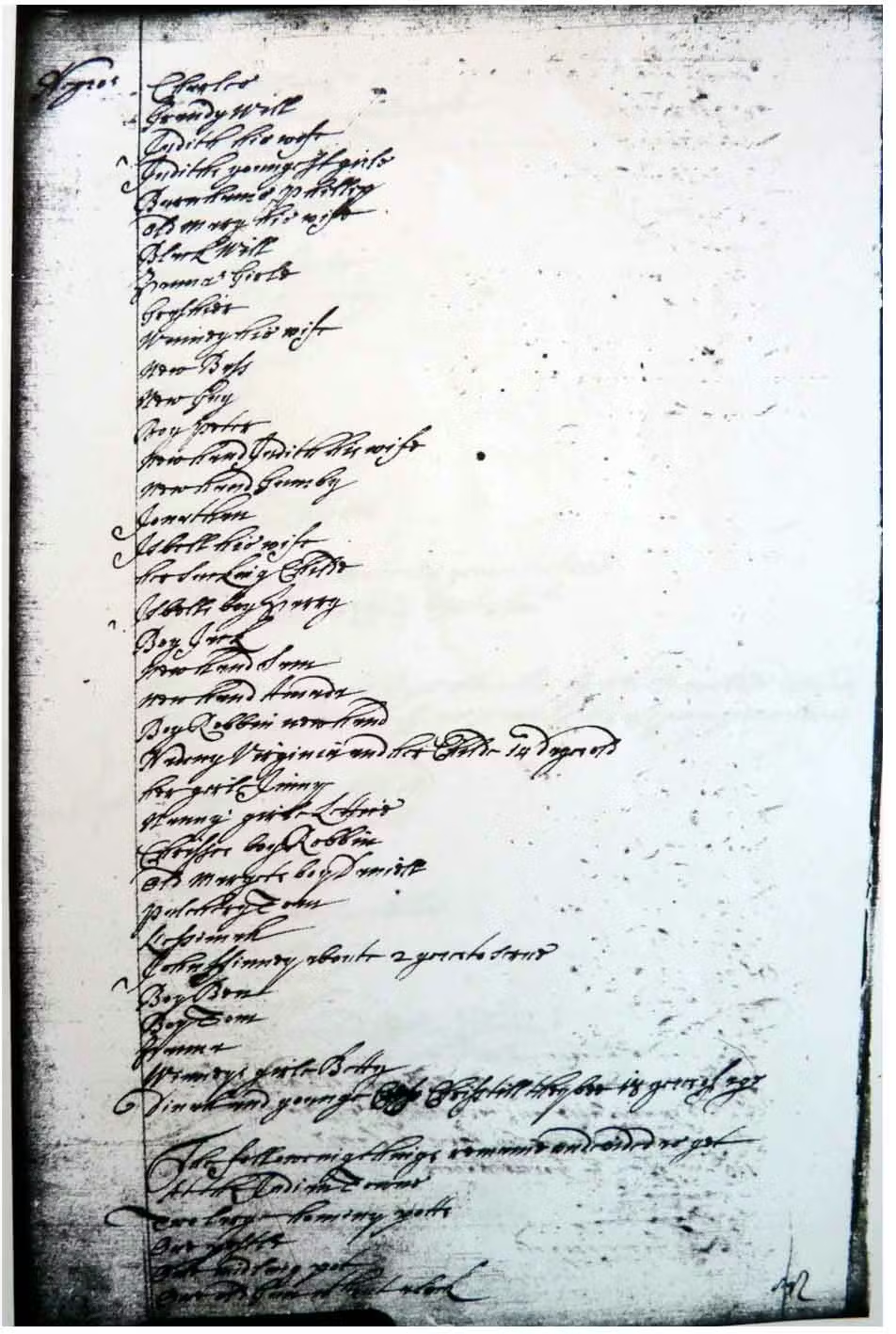

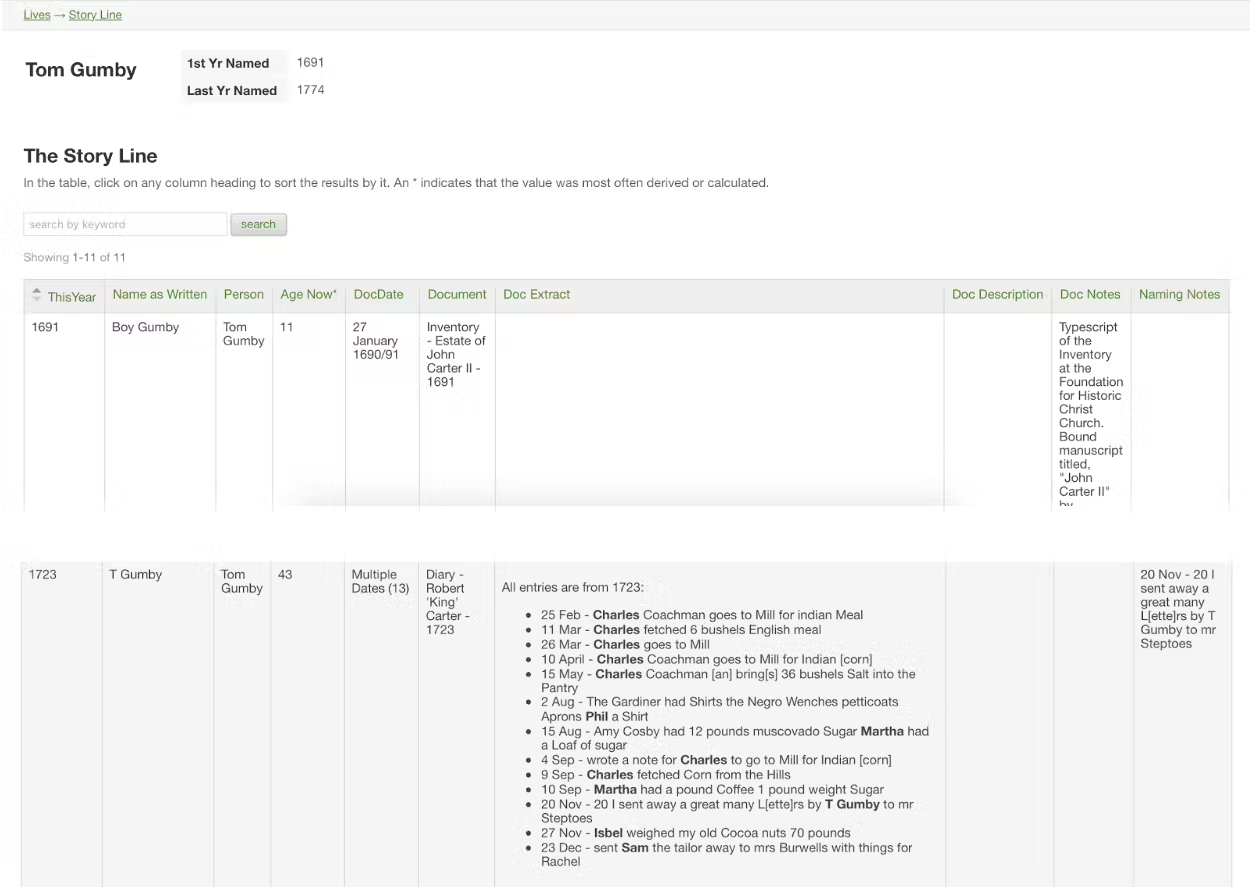

As it turned out, this woman knew she was a descendant of a slave named Tom Gumby.

“It’s really rare to have a surname for a slave,” Patrick explained, and that detail inspired him to search his database for the woman’s ancestor. He found references to Tom Gumby across his records.

In 1691, the man appeared as “Boy Gumby.” From that reference, they were able to determine his age, which enabled him to look for Gumby, T. Gumby, and other variations on his name found throughout the following years.

Tom Gumby reference.

“To her delight,” explained Patrick, the woman had stumbled upon a rich history of her earliest known ancestor. That listing was as close as one might get to finding a record of his birth. “It was a moving moment both for the descendant and for me,” Patrick said. “Even if this work were to prove beneficial to nobody else, it thereby proved worth all the effort to me.”

It was a moving moment both for the descendant and for me. Even if this work were to prove beneficial to nobody else, it thereby proved worth all the effort to me.

Adding Pieces to the Puzzle

Knack is much more than a simple database for storing records. Knack provides tools to organize, search, browse, and filter the data in a variety of ways. This has led Patrick to make historical assessments that otherwise would have remained lost in a sea of data.

The period Patrick’s research focuses on is “remarkably rich with references in surviving documents.” For that reason, he explains, gathering and analyzing these references may help historians better understand the larger framework of that time.

Patrick has already been able to help make judgments based on analyzing the data in his Knack app. Thanks to its organization and his ability to query the data, he was able to write a paper demonstrating that a large increase in references from the late 17th century to the mid 19th century had more to do with childbirth than with purchases of new slaves.

“This work has revealed all sorts of things that I’m certain would not have been revealed to me otherwise,” Patrick says. At the outset, there was almost too much information to take in. Now, with the help of his Knack database, one can seek it out simply and efficiently.

Onwards and Upwards

In spite of the amount of work the project has demanded, Patrick’s passion hasn’t slowed and neither has his appreciation of Knack. He’s found the support of the team to be especially valuable. “You really do care,” he says, “I just felt that from the start and still do.”

The success Patrick has had with Knack has led him to expand his plans for the future. In a few months, he hopes to have a similar project on indentured servants up and running. This database will echo the Corotoman slave histories in many ways, allowing public access to expansive historical records from the region.

In the area and time period Patrick is studying, these indentured servants were primarily white Europeans. In exchange for having their passage to the colony paid, they agreed to work for a plantation owner for a certain length of time.

The Virginia colony was also required to stay on top of the division of land, and parishes were required to walk each colonist’s boundaries along with witnesses, to categorically gather data on every property.

The Historic Christ Church in Weems, Virginia.

As a result of this process, there are detailed Christ Church Parish records from 1715 to 1783. Patrick’s plan is to eventually have a similar searchable database that grants access to land and property records of Historic Christ Church Parish.

Patrick has already accomplished a great deal with his research. His Corotoman slave histories encompass more than 4,000 reference to slaves from the estate. With the help of over two hundred documents from 1656 to 1862, he has been able to identify more than 1,200 individual slaves, gathering details on each one into an easily searchable database.

Yet despite everything he’s achieved, Patrick is only getting started with Knack. “I have been continuously delighted by learning things that I can do with it,” he says.

The end, in other words, is nowhere in sight.